“I was walking along a shoreline together with my mother. The weather was nice; the wind was blowing and I could hear the waves crashing on the beach. I was talking with my mother, but I don’t remember what the topic was. Suddenly, my mother stopped and turned to me. She smiled and said: ‘You do know you are dreaming right now, don’t you?'”

At this point in the narration of the dream, I have many questions. “Why was it your mother….or was she just….did you wake up?” Apart from the confused stuttering, I’m also a little uneasy. Being suddenly jolted into self-awareness during a reverie sounds like it may not be the most pleasant of experiences. André Keizer lets me know that it’s actually quite the contrary. “Having a lucid dream is an awesome experience,” he explains. “When you gain control over the contents of your dream, the possibilities are endless: you can fly, walk through walls, and talk to your most inner self or even long-lost friends.”

We all have dreams, but Keizer understands them better than most. The Dutchman has a background in cognitive neuroscience, with published scientific papers dealing with topics relating to memory, consciousness, binding processes, and cognitive control. More recently, his work at the Neurofeedback Institute in the Netherlands has focused on neurofeedback in clinical applications.

Keizer, along with Derk Mulder also of the Neurofeedback Institute, is the creator of The Lucid Dreamer. The device—which claims to be able to induce lucid dreams consistently—is an application of recent research into current stimulation techniques as a means to achieve self-awareness while we sleep.

Tell Me My Dreams

A lucid dream is a kind of dream in which the dreamer becomes aware that they are, in fact, dreaming. On gaining cognizance of what’s going on, one may be able to exercise some level of control over the environment or narrative. And it’s not just like waking up in a movie or being inside a video game; proponents believe there are very real benefits to the experience.

In his beginner’s guide to lucid dreaming, Tim Ferris explains how he trained with 2-time Olympic champion wrestler John Smith in high school. Ferris went on to have his best season that year, managing to rack up a 20-0 record in the run up to the nationals. Well of course he did; he trained with one of the most decorated wrestlers of all time. But not quite. The twist in this tale is that Ferris never actually met John Smith while training under him. Instead, he used his time in lucid dreams to practice the wrestling virtuoso’s signature moves.

Ferris’ claim may sound like new-age hokum, but there’s actual scientific evidence to suggest that lucid dreams serve as fertile settings for skill acquisition. In a paper titled Practicing a Motor Task in a Lucid Dream Enhances Subsequent Performance, German researcher Daniel Erlacher showed how subjects got better at tossing coins into coffee cups by waking up inside their dreams to practice. Erlacher now works at the University of Heidelberg’s Institute for Sport and Sport Science, using his research to enhance athletes’ performance in unconventional ways.

The benefits of lucid dreaming aren’t limited to motor tasks. Stanford PhD Stephen LaBerge has shown through his research that the practice boosted creativity, problem-solving skills, and learning abilities. Inside the world of your own dreams, you can write a song, solve a math problem, or rehearse a speech. Not just that; you can carry what you’ve gained back to the real world.

The Science of Being Lucid

With scientifically documented benefits and a lot of exhilarating fun being promised, André Keizer wondered if he could come up with a way to consistently induce lucid dreams. His partner in the undertaking was Derk Mulder, an accomplished neuroscientist who is the founder of the Neurofeedback Institute in the Netherlands. “Having tried different techniques and devices, we always hoped there would be a more effective way of inducing lucid dreams,” Keizer recounts.

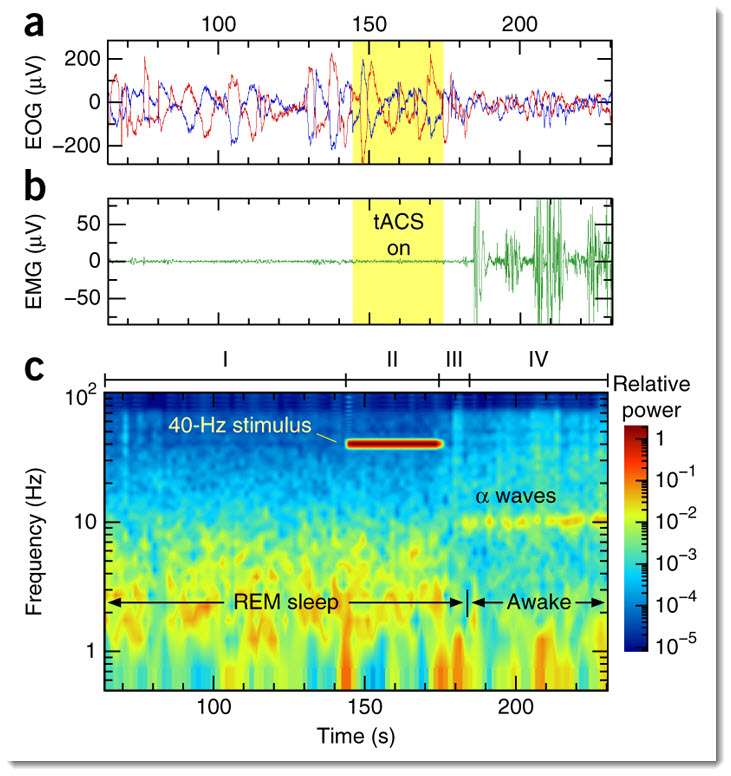

The duo’s big break came in 2014, when a groundbreaking paper in Nature Neuroscience demonstrated a novel way in which lucid dreams could be induced. A specific brain phenomena known as gamma activity was the focus of the research. The team of scientists from Germany was able to show that administering a form of electrical stimulation called tACS (Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation) during REM sleep (a phase of sleep during which mammals are known to have vivid dreams) “induces self-reflective awareness in dreams.”

“We immediately realized that this technology had the potential to revolutionize the way people dream,” Keizer says. Their confidence was well-founded, since the technique delineated in the paper showed that tACS could induce lucid dreams 77 percent of the time. Guided by the work laid down by their peers, Keizer and Mulder set about finding a way to develop the lab-based methodology into a mass-market product.

Lucid Dreams in a Box

The result of their work is The Lucid Dreamer, a device about the size of a matchbox. It is capable of inducing lucid dreams by first detecting the onset of REM sleep, and then applying tACS. “The Lucid Dreamer uses the exact same technique as was described in the seminal paper and combines it with the automatic detection of the onset of dreams, based on the measurement of brain activity using EEG [electroencephalogram],” Keizer explains.

The Lucid Dreamer applies the electrical stimulation that triggers the process using disposable electrodes. Users place the device on their forehead; they then adhere four electrodes to the forehead area, and two over the mastoid region (behind the ears). The next step is to fall asleep. During that time, the device detects when you’ve entered REM sleep, and proceeds to apply the tACS current. Lucid state achieved. Well, most of the time.

“We have successfully tested the Lucid Dreamer and have demonstrated it to induce lucid dreams consistently in a small group of volunteers,” Kaizer tells me. Encouraged by the positive results they were able to achieve in tests, the team proceeded to package The Lucid dreamer into a commercial offering. Creating a mobile app to go along with the specialized hardware was an important part of that process.

The Lucid Dreamer app is used to guide users through a cognitive exercise known as MILD. MILD—or the Mnemonic Induction of Lucid Dreams—is a technique created by Stephen LaBerge. It trains individuals in self-awareness methods that make it simpler to recognize when a dream is underway. The app also allows users to tinker with the frequency and duration of the electrical stimulation, which often results in very different kinds of dreams.

The various frequencies and durations with which users can mess around in the app are called stimulation protocols. As Keizer explains, “After we start shipping the Lucid Dreamer, more and more people will experience The Lucid Dreamer with customized stimulation protocols, which they can share in an online community.” The feedback from the online community will be used to further their research into dreams and consciousness.

The Lucid Dreamer has crossed its Kickstarter goal of €100,000 (~109,000 USD), now having raised over €134,000 (~146,100 USD). Each unit comes with 25 sets of electrodes, which are good for 25 nights of lucid dreaming. Users will have to purchase electrodes separately once the initial sets run out. Each set of six electrodes required for a night will cost about $1.

If what Keizer tells me of his experiences with the product is true, it sounds very exciting: “I’ve had lucid dreams in which I could go full-Superman; I could fly around and even teleport.” Teleportation isn’t even one of Superman’s abilities, but I guess that’s the power of a dream.

—–

Editor’s Notes:

As this article was being edited, the Kickstarted campaign was “canceled by the project creator.” We are looking into the details of this event. SnapMunk has also reached out to independent neuroscience experts for their thoughts on The Lucid Dreamer. The article will be updated on receiving their responses.

—–