On the 31st May this year, Swiss startup Climeworks made carbon capture history when it launched the world’s first commercial-scale Direct Air Capture (DAC) plant, featuring its patented technology that filters carbon dioxide from ambient air.

Circular Economy Vision

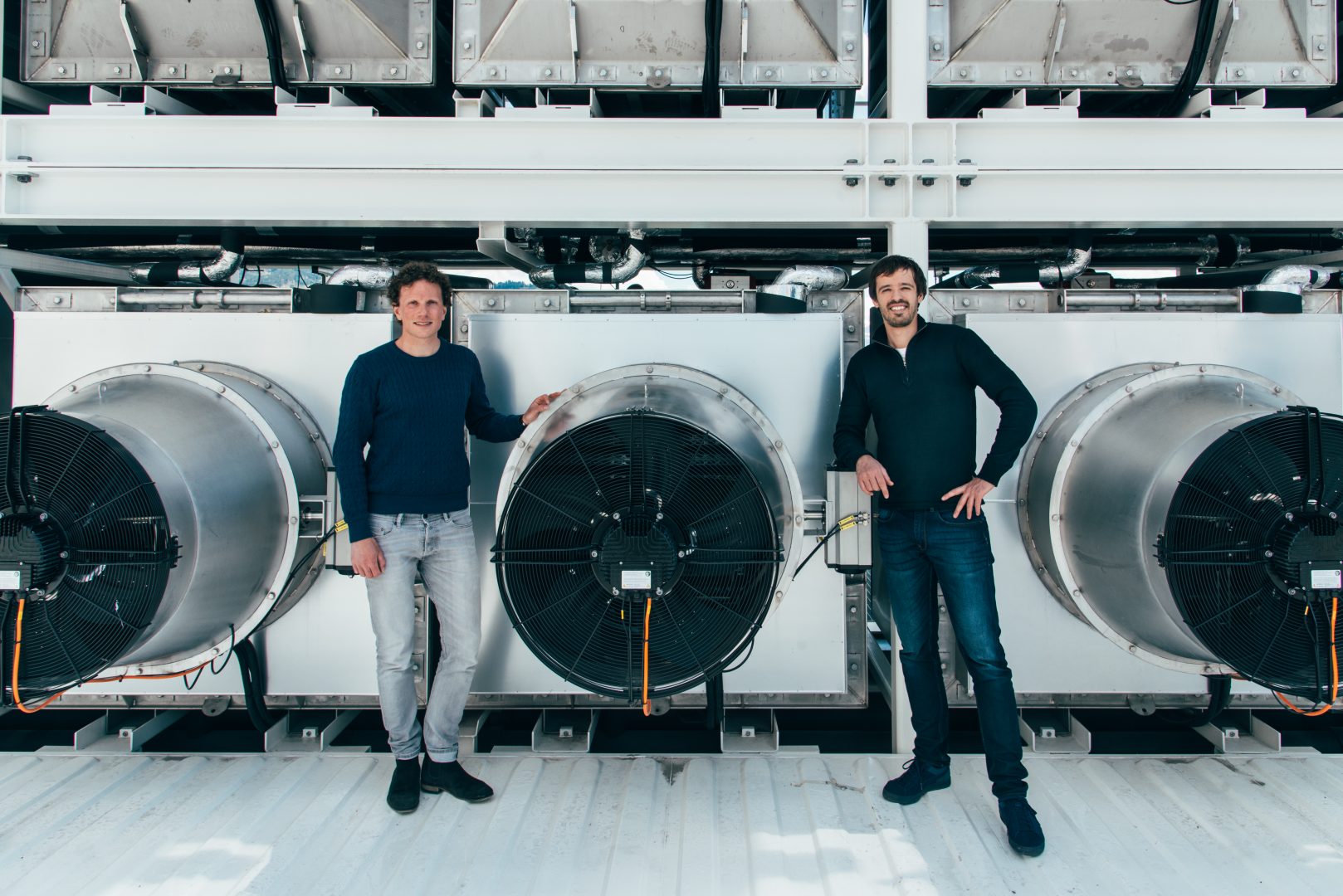

When engineers Christoph Gebald and Jan Wurzbacher met on their very first day at the prestigious Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, Switzerland, they made a pact to found a company together. Their first business plan for the company that would become Climeworks was for a venture challenge course at the University. Fast forward nine years to today and their first carbon capture plant is up and running, in Hinwil, Switzerland.

“We are breaking down the circular economy approach to an atomic level,” Valentin Gutknecht, Climeworks Director of Marketing and Communications told SnapMunk. “Carbon is a central building block of the economy, and with our CO2 capture plants, we are closing the carbon cycle. One possibility is by providing renewable CO2 to greenhouses. Another one is to produce renewable hydrocarbon fuels out of air captured CO2 or to produce plastics.”

How It Works

Climeworks’ technology captures atmospheric carbon with a filter, using mainly low-grade heat as an energy source. In Hinwil, the DAC plant was installed on the roof of a waste recovery facility – with its waste heat powering the plant while fans on the outside suck in the ambient air. Inside each of the eighteen collector units, the air goes through a process of adsorption and desorption before being blown out again with reduced CO2 content. The process captures 2,460 kilograms of CO2 per day, depending on factors such as weather conditions and air composition. In total Climeworks will sell 900 tons of CO2 annually at market prices to a nearby greenhouse to help grow vegetables.

During the Climeworks capture process, CO2 is chemically deposited on the filter surface. Once the filter is saturated, the CO2 is then isolated at a temperature of about 100 °C. The pure captured CO2 gas can then be sold to customers in key markets, including: commercial agriculture, food and beverage industries, the energy sector and the automotive industry. By using Climeworks’ CO2, customers can reduce their overall emissions as well as lower their dependence on fossil energy.

First Commercial Customer

In Hinwil, Climeworks provides a continuous supply of CO2 through an underground pipeline to a greenhouse 400m away, to assist with growing vegetables such as tomatoes and cucumbers, which are then sold via major Swiss retailers including Migros and Coop. The Hinwil plant will operate as a three-year demonstration project/use-case.

In coming months Climeworks plans to launch additional commercial pilot projects in those key target markets and wants to test the technology’s potential to deliver negative emissions by combining it with underground storage. “With the energy and economic data from the plant we can make reliable calculations for other, larger projects and draw on the practical experience we have gained,” said Jan Wurzbacher, Climeworks co-founder, and managing director.

Unlocking A Negative Emissions Future

“Highly scalable negative emission technologies are crucial if we are to stay below the two-degree target of the international community,” said Christoph Gebald, co-founder and managing director of Climeworks. “The DAC-technology provides distinct advantages to achieve this aim and is perfectly suitable to be combined with underground storage. We’re working hard to reach the goal of filtering one per cent of global CO2 emissions by 2025. To achieve this, we estimate around 250,000 DAC-plants like the one in Hinwil are necessary.”

Compared to other carbon capture technologies, DAC does not depend on arable land, has a small physical footprint, and is fully scalable. Plants are modular and can be located independently of emission sources, allowing security of supply wherever there is atmospheric air.

Avoiding The Worst Impacts Of Climate Change

Air capture and other harmful emissions technologies have been called an “unjust and high-stakes gamble,” by scientists concerned that these technologies will distract the world from viable climate solutions. Meanwhile, others have made the point that it’s cheaper to perfect carbon capture directly at fossil fuel plants and keep CO2 out of the air in the first place.

Supporters of a technological solution say that it’s just a matter of lowering costs. In 2007 Sir Richard Branson launched the Virgin Earth Challenge and offered $25 million to the builder of a viable air capture design. Climeworks was one of the 11 finalists, as were companies like Carbon Engineering, which is backed by Microsoft Corp. co-founder Bill Gates and is testing air capture at a pilot plant in British Columbia.

“That scientists are even considering technological interventions should be a wake-up call that we need to do more now to reduce emissions, which is the most effective, least risky way to combat climate change,” said Marcia McNutt, editor-in-chief of Science and former director of the U.S. Geological Survey. “But the longer we wait, the more likely it will become that we will need to deploy some forms of carbon dioxide removal to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.”

As the debate continues as to whether carbon capture technology can truly play a significant role in removing greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere, by this time next year, Climeworks’ will have removed 900 tons of CO2 from the atmosphere. As the expression goes, filtering one per cent of global CO2 emissions by 2025 starts with the first 900 tons.