A few months ago, we covered the pay-per-article media platform Blendle as a rare glimmer of hope in the dismal world of journalism. They had just released their platform in the United States after amassing impressive user numbers in the Netherlands and Germany. Last week they reached 1 million users. The all-important “daily active users” count (a concept covered brilliantly last season in Silicon Valley) is supposedly in the 100s of thousands, although they refuse to release actual figures.

That success can’t all be attributed to the U.S. market though. The beta version in the States only included 10,000 subscribers, and now there’s a waiting list of over 25,000. Lack of news is still good news in the fraught journalism space though, and the fact that the app is steadily growing is relatively promising.

Especially when you consider that Blendle is trying to solve a monetization puzzle that Silicon Valley nerds have been working on since the genesis of the Internet. Publishers missed their chance when free content became the norm in the early 2000s, and it failed when the New York Times and Atlantic Monthly attempted to monetize in the late 2000s. Most insiders seem to assume, rightly or wrongly, that it will fail again.

“Information Wants to be Free”

Stewart Brand told Steve Wozniak:

“On the one hand information wants to be expensive, because it’s so valuable. The right information in the right place just changes your life. On the other hand, information wants to be free, because the cost of getting it out is getting lower and lower all the time. So you have these two fighting against each other”

Blendle’s outside-of-Silicon-Valley mindset might be the only reason they’re willing to take up the fight to make information cost something. The Dutch entrepreneurs Marten Blankesteijn and Alexander Klöpping, who founded the company two years ago, think that the fetishism of “free content” actually discourages the creation of high-quality information. Rather than fueling creativity from the bottom, it becomes a race to the depths, with websites competing over the tiniest margins, putting out multiple stories a day instead of focusing on reporting and investigating.

Blendle points to their subscribers, over 20% of whom are actually using the paid service, as evidence that this trend is not a foregone conclusion.

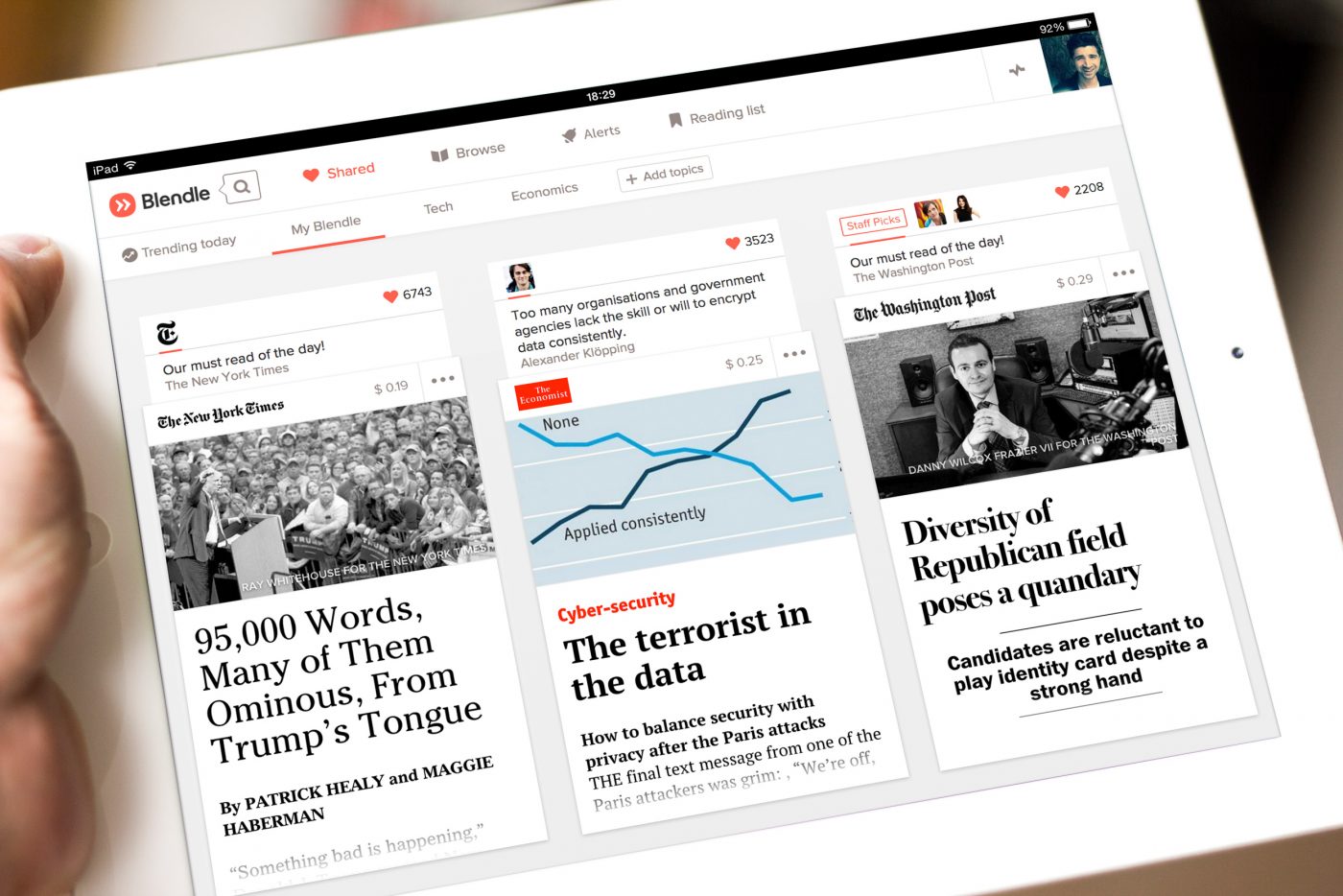

Blendle owes much of its success to the fact that it uses actual human curation across over 20 different publishing companies. Taking a page from content-curating newsletters like theSkimm, Blendle selects a few high-quality pieces and delivers them on the front page of the app. These are mixed in with articles that are automatically picked based on metrics like length, topic, and complexity. Once a user clicks on one of these tailored selections, they’re automatically charged 19-39 cents. Magazine articles can go for as much as 49 cents. Either way, you’re only paying for vetted content that you choose to read. It’s the equivalent of iTunes breaking up albums into individual purchasable tracks, assuming those tracks have actually been bubbled up for their quality and appeal.

If Blendle’s curation and selection rope people in, the money-back guarantee keeps people coming back. If you don’t like an article, even if you just don’t agree with it, you can get a refund. This shifts the decision moment from the beginning of the read to the end, making customers more likely to take a chance. Klöpping claims that this puts readers at ease while also incentivizing writers to invest in really strong reporting, since they run the risk of losing a micropayment every time they turn a reader off. Only about 10% of their users take advantage of this guarantee.

That kind of instantaneous monetary feedback is rare, and possibly nonexistent, in journalism. It brings to mind services like Twitch, which allow viewers to make micro-donations on channels they like based on the quality of what they’re seeing. Blendle doesn’t have the ability to give these micro “tips” to articles yet, but allowing refunds accomplishes a similar purpose. It starts at the level of one article and one writer, but if effectively executed and appropriately adopted, it has the ability to rippled to much deeper layer of the industry and the perception of those who fund it.

The Paywall Problem

One major concern with Blendle is sharing. Since everyone on the internet isn’t signed up to make micro-payments, spreading articles virally through Blendle becomes more difficult. Any pay-to-enter service will ultimately suffer from this. It’s Blendle’s biggest challenge to overcome: how do you get people to enter their payment information, like they do on Spotify, Audible, iTunes, and other premium services. Especially in the context of an unexpected “share” consumption. With a little creativity and flexibility on the technical side, and the right amount of desparation on the production side, it’s not an insurmountable issue, but one that certainly pumps the brakes.

Is Journalism Cute Puppies or Iraq?

John Oliver painted a sad picture of the state of journalism in a recent episode of Last Week: Tonight. He ended with a clip of Sam Zell, who ran the Tribune Company into bankruptcy and laid off more than 4,200 employees; the clip showed him attacking a question from an audience member regarding the intrinsic merits of click-hungry content.

Zell angrily defended the strategy by explaining that as a consumer service, they must provide what readers want—even if that means running stories about “puppy dogs” instead of insights into global politics and civil conflict. “Hopefully we get to the point where our revenue is so significant,” he said, “that we can do puppies and Iraq, OK?” He then added, “Fuck you.”

Fuck you indeed! You insubordinate journalists who accept minimal pay for long hours! Who complain when they’re arbitrarily fired! Who want to tell stories that matter, even if they’re more difficult and more expensive to fund! FUCK YOU!

I think it’s fair to say there’s a hostile environment towards journalists. Blendle was founded by journalists, and their small but nonetheless impressive subscriber base is the one bit of good news John Oliver’s reporting was missing.