It has been called many things; universal basic income, guaranteed minimum income, guaranteed basic income, etc. It all means the same thing: the government cuts you and every other adult a check for the same amount every month, simply because you’re a living, breathing citizen. No eligibility requirements, no paperwork, no restrictions on how you spend it. It’s money you “earn” simply by being born.

The idea isn’t new. Thomas Paine suggested something like it back in 1795, and he almost certainly wasn’t the first to come up with it. Plenty of other political and economic luminaries have chimed in with their support of some flavor of universal basic income since then, including politically conservative free market economist Milton Friedman—one of the most famous and respected economic minds of the twentieth century.

Of course, it has never really been tried for a variety of reasons. Chief among these are the questions of how to pay for it and what people will do if they don’t have to work a full-time job to earn “a living.” And these are fair questions, fraught with many factors far too complex for even a brilliant novice like myself to master. But answering the first question, while it makes for an interesting debate, is a far less pressing task when we consider the assumption beneath the second question—the assumption that people can earn a living by working a full-time job.

This is increasingly not the case in many occupations, and that situation is about to get a whole lot worse.

No Money, Mo’ Problems

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the median household income fell 8% between 2007 and Fall of 2014. Yes, the Great Recession hit in 2008, but “recovery” happened in 2009-2010. The majority of American households haven’t bounced back, even though unemployment is roughly back to pre-recession levels.

As of 2014, median household income was $53,657, of which we can conservatively assume about 20% goes to taxes (including federal and state income tax, Social Security, and Medicare, and not counting sales tax), leaving $42,926 in take-home pay. Median rent per household is $934 per month, or $11,208 annually—our typical American household is down to $31,718 in “disposable income.” Health insurance premiums can eat up more than half of that, though that gets complicated with employer contributions and tax credits.

All told, though, the average household in the US is looking at less than $2,000 each month to pay for food, utilities, transportation, clothing, and NASCAR tickets. No matter where you live, it’s getting tough. And we haven’t even reached the bad news yet.

The Jobs We Have Aren’t Sticking Around

As hard as it may be to scrape together a living today, it’s going to be even harder tomorrow. Because the robots and computers that are taking over our jobs are a whole lot cheaper, and the jobs they’re taking aren’t being replaced.

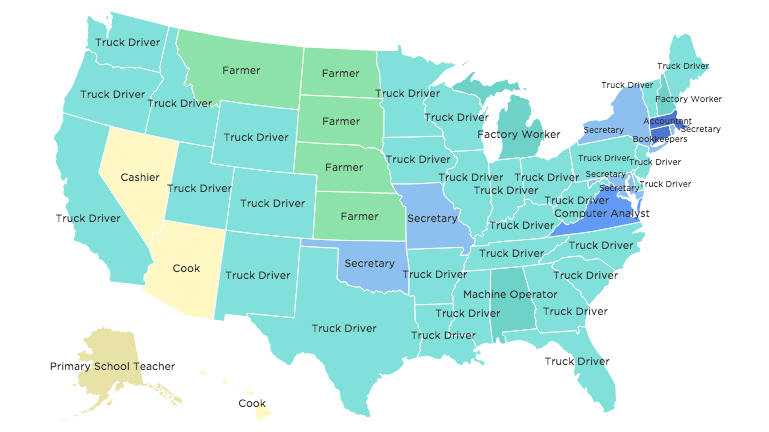

Take truck drivers, for instance. This NPR article and map has made the social media rounds a few times since first appearing early in 2015, and though its conclusions have been called into question, it raises an interesting case study.

Whether or not “Truck Driver” is the most common occupation in every state, there are a lot of them—around 3 million, depending on who you ask. And they support plenty of other businesses, from fast food to hotels to gas stations to lot lizards. Self-driving trucks, like the ones made by Uber-bought OTTO Motors, will not only erode millions of truck driver jobs, but the computers driving them won’t need roadside burgers, sleeping quarters, or meth-fueled handjobs. And if Blacktop Betty can’t meet her quota, you can bet we’ll be picking up her tab at the ER, too.

In short, self-driving trucks are going to have a substantial impact on employment—not just in localized communities but nationwide.

Same Same But Different?

Now, the same dire warnings were issued when highways and airplanes started replacing railway lines, it’s true. It’s also true that while many towns did shrivel up and die when their railway went away, the new technologies provided plenty of new jobs to balance things out on the macro scale. But it’s also also true that automated equipment like self-driving trucks don’t really create any new jobs—they’ll need no more maintenance than your typical truck today, and with fewer accidents and more precise controls they may even need less.

The same thing is happening in other industries, too. Retail sales jobs are giving way to automated screens and online purchases. Customer service is being delivered remotely (if at all) from massive call centers that increase efficiency and thus reduce the number of employees needed. 3D printing is going to eliminate many manufacturing and construction jobs in the coming decades; a handful of operators and maintenance providers will be needed instead of the massive workforces these industries require today.

Some argue that a better educational system would better prepare the next generation for the types of jobs we’ll actually need, and that’s a valid point. Brainwork (and creative work, to a degree) will be the work work of the future, especially in the developed world. But those jobs will never exist in abundance unless we quickly ramp up whole new industries like space mining and manned space exploration; or invest heavily in ongoing infrastructure improvement projects.

Both of those require massive amounts of government spending on par with a universal basic income, and are seen as even more distasteful departures from the free market by many of the powers that be. Even then, without a liberal dose of negative eugenics we’d likely just be kicking the can down the road.

Our options are simple. One is to make up work for people to do and then pay them for it, which is as anti-market a solution as anything. Another is to give people a basic minimum income so they can buy the things automated helpers are producing and delivering without the busywork of a made-up job. Finally, we can let our society devolve into the extremes of haves and have-nots and wait to see if a Snake Plissken-like avenger arises from the starving masses.

I’ve got no beef with Kurt Russell, but I’m not sure he’s the man I want in charge of my economic future.